Having successfully completed last year's New Year's Resolution to post every Friday on this blog, I thought I'd mix things up again for 2014. I'll be keeping my regular Friday posts, but adding a Monday Musings slot where I briefly discuss topical book and writing-related questions (e.g. is 'writing what you know' necessarily a good thing? What do we mean by 'showing not telling'?) Wednesday will become a 'wild card' day where I may post or not, depending on how much I've been reading recently - I hope to occasionally do reading round-ups, for example.

Having successfully completed last year's New Year's Resolution to post every Friday on this blog, I thought I'd mix things up again for 2014. I'll be keeping my regular Friday posts, but adding a Monday Musings slot where I briefly discuss topical book and writing-related questions (e.g. is 'writing what you know' necessarily a good thing? What do we mean by 'showing not telling'?) Wednesday will become a 'wild card' day where I may post or not, depending on how much I've been reading recently - I hope to occasionally do reading round-ups, for example.

That said, here's the schedule for regular posts in January:

Friday 3rd January: Fallout by Sadie Jones

Friday 10th January: Tigers Nine: The Night Guest by Fiona McFarlane

Friday 17th January: The Signature of All Things by Elizabeth Gilbert

Friday 24th January: Farthest North and Farthest South #6: Non-Fiction Medley

Friday 31st January: This Book Will Save Your Life by AM Homes

It's time again for me to consider my favourite books read by me for the first time in 2013 - although, unusually, this year's list includes more 2013 prizewinners and shortlistees than I've ever had before. Either prize juries are becoming more effective or my tastes are becoming more conventional… In no particular order:

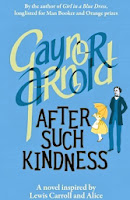

1. After Such Kindness by Gaynor Arnold.

I reviewed this novel, inspired by the relationship between Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, in January. I enjoyed her Girl In A Blue Dress, but for me, this heartbreaking narrative of the scars we carry and the scars that do not heal was in a different league. It's not received the critical attention that it deserves, but I hope it will go on to find many readers. I was also impressed by her sensitive handling of her stand-in for Lewis Carroll.

2. The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt.

2. The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt.

An obvious choice, but this novel really is exceptional, as I detailed in my initially cautious first impressions and my positive final verdict. Tartt's novels are always magnificently flawed, and this is no exception - but by the final pages, I felt she had fully earnt the risky conclusion. Theo's journey from the death of his mother in an explosion in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to dabblings in dodgy antiques is overlong but nevertheless brilliant. (Tartt pulls off a perfect portrayal of PTSD along the way, as well). In 'the year of the doorstopper' this reminded me yet again why I love long novels.

3. Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver.

This was my choice for The Prize Formerly Known As The Orange, and although I liked the winner - AM Homes's May We Be Forgiven - for me, this stood out. Kingsolver, despite previous form, is astoundingly unpreachy in this tale of how climate change impacts upon a small community in the Appalachian mountains. It's not necessarily an easy read, but it is a rewarding one. (And am I the only one who feels that the 'Bailey's' Prize is not going to be the same? I'm convinced the Whitbread went downhill after becoming the Costa…)

4. The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton.

4. The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton.

To wheel out another doorstop, this was my choice for the Booker and I was thrilled that it won, especially as it saw off some truly terrible efforts from Jim Crace and Colm Toibin. This novel, set in the nineteenth-century New Zealand gold rush, is a complicated, dense narrative that repays close attention, but will certainly be appreciated by those who love the original nineteenth-century doorstops. Although they have so often been paired in end-of-the-year lists, Catton's meticulously constructed mechanism is nothing like Tartt's generous storytelling. But, somehow, they both work.

5. Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

This was another novel I wasn't sure I'd like, especially as I wasn't swept away by any of Adichie's previous works. But Adichie combines all her previous talents into one in this massive story of childhood sweethearts Ifemelu and Obinze, seeking to emigrate to the West to seek the opportunities that are not available to them in Nigeria. One reason why this fantastic exploration of race in the US and Britain hangs together is because their simple love story runs through its heart. However, Adichie's social observations are vital as well.

6. A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki.

This didn't sound like my kind of thing at all - I expected it to be needlessly experimental, saccharine and/or trite. But I loved the tenuous links between the two narrators, and the way the novel plays with time and space. The obligatory references to Schrodinger's cat are perhaps a little obvious, but I loved the footnotes and the way that every page seems joyful and alive, despite some dark narratives. I never expected this to win the Booker, but it would certainly be my runner-up.

7. The Worst Journey in The World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard.

7. The Worst Journey in The World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard.

2013 wasn't just about prize lists, however. This 1922 account of Antarctic travel, including Scott's last expedition and Cherry-Garrard's own insane quest to recover emperor penguin eggs, is rightly acclaimed as a travel classic. Cherry-Garrard conveys the horror, humour and beauty of the Antarctic in wonderfully accessible prose.

8. Bring Up The Bodies by Hilary Mantel.

8. Bring Up The Bodies by Hilary Mantel.

Although I appreciated Wolf Hall on an intellectual level, I found it a slog; the narrative never seemed to spark into life, although the portrayal of Thomas Cromwell was exceptional. Having read its sequel, I now think that all the preparation was worth it, because Mantel hits the ground running in Bring Up the Bodies. Having established the cast, she can indulge in the historical drama of the fall of Anne Boleyn without the need to explain the context.

9. The Life of Charlotte Bronte by Elizabeth Gaskell.

9. The Life of Charlotte Bronte by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Although I'd read all of Gaskell's novels (bar Sylvia's Lovers, which I am reading now) I have never read her biography of Charlotte Bronte. I'm not a Bronte obsessive - I adore Villette but am ambivalent about Jane Eyre, and actively dislike the novels of the other Bronte sisters - and so I'd never seen reason to read this. However, despite its bowdlerisations, this biography conveys the timeless story of the Brontes' short lives vividly. It was the only novel in my top ten I didn't review on the blog this year, so I've linked to my review of Villette instead, where I talk a lot about this biography.

10. Quantum by Manjit Kumar.

10. Quantum by Manjit Kumar.

To be honest, there wasn't a tenth book this year that made an impact on me equal to the previous nine. But Manjit Kumar's history of the debates between Einstein and Bohr is both absorbing and accessible, and I enjoyed the mini-biographies of the scientists' lives as well as the clear explanations of the content of their debates.

As for stats, I read 102 books this year, beating both the previous years' records - I blame this blog.

For Ginny Cook Smith, her father's thousand acres has been the bedrock of her life in Iowa, the ground upon which her life, and the lives of her two sisters, Rose and Caroline, and their families has been built. However, early in the novel, her description of 'tile', the plastic tubing that has drained the soil and made it fit for crops, indicates a hidden instability underneath the universal currency of land: 'I was always aware, I think, of the water in the soil… the sea is still beneath our feet and we walk on it.' It is only later in life that Ginny becomes aware of the possible link between the nitrates draining into their well water and the five miscarriages she has suffered, but the image of the underground lake lingers. However, it is also the deep roots of this novel in a particular type of community and its affiliation to the land that allows it to escape both melodrama and the accusation that it is simply a poor reworking of King Lear. Although the parallels with Lear are, in one sense, obvious - the plot hinges on Larry Cook's division of his farm between his two oldest daughters after he cuts the youngest out of his will - I found that as I read I forgot the links with the play and that obvious references failed to occur to me until after I'd finished reading. This is obviously a good thing; and testament to Smiley's excellent writing that incidents that could have seemed grotesque or ill-fitting in a modern-day retelling, such as 'Gloucester's' blinding or Goneril's rumoured poisoning of Regan, worked seamlessly within Ginny's narrative.

For Ginny Cook Smith, her father's thousand acres has been the bedrock of her life in Iowa, the ground upon which her life, and the lives of her two sisters, Rose and Caroline, and their families has been built. However, early in the novel, her description of 'tile', the plastic tubing that has drained the soil and made it fit for crops, indicates a hidden instability underneath the universal currency of land: 'I was always aware, I think, of the water in the soil… the sea is still beneath our feet and we walk on it.' It is only later in life that Ginny becomes aware of the possible link between the nitrates draining into their well water and the five miscarriages she has suffered, but the image of the underground lake lingers. However, it is also the deep roots of this novel in a particular type of community and its affiliation to the land that allows it to escape both melodrama and the accusation that it is simply a poor reworking of King Lear. Although the parallels with Lear are, in one sense, obvious - the plot hinges on Larry Cook's division of his farm between his two oldest daughters after he cuts the youngest out of his will - I found that as I read I forgot the links with the play and that obvious references failed to occur to me until after I'd finished reading. This is obviously a good thing; and testament to Smiley's excellent writing that incidents that could have seemed grotesque or ill-fitting in a modern-day retelling, such as 'Gloucester's' blinding or Goneril's rumoured poisoning of Regan, worked seamlessly within Ginny's narrative.

Ginny and Rose share the memory of a tormented childhood under Larry's watch, especially after the death of their mother, and Smiley deftly conveys the pain they have both concealed while resorting to very little direct detail from either of this sisters. It is, indeed, one of Larry's mismemories as he descends into madness that provides one of the most vivid images of the past, when he tells Caroline about a brown velveteen coat she once had: 'You didn't like it either, nosiree. You didn't want any brown coat and hat. You wanted pink! Candy pink. You had it all worked out in your mind about that pink velveteen, and you took a pink Crayola to that coat, too!… Your mama had to spank you then for sure!' Ginny, who overhears this exchange, cannot bear it when her father brings this story up again in a court case, after the tables have turned and Larry believes that Caroline is the only daughter who is on his side. Confronting him with the fact that he has reshaped their past, she shouts, 'Daddy, it was Rose who had the velveteen coat! It was Rose who sang! It was me who dropped things through the well gates!' This brief thread demonstrates a number of things about Larry's relationship with his daughters; that he can continually reinvent himself as the loving patriarch, focusing on their mother's light spankings rather than his beatings; that he prefers to forget his daughters' existence rather than recognise what he sees as their disloyalty; and that despite recognising his abuse, Ginny and Rose remain desperate for their father's love.

Despite knowing the plot, I have not read or seen King Lear, and now I would like to see it with this very different take on the story fresh in my mind. Smiley's choice to humanise the two older daughters is not merely a cheap switch in perspectives but allows her to explore the tale afresh, rebuilding it from within to consider the entrapping effect of family ties. Near the end of the novel, Ginny escapes for a few years to an anonymous life working in a highway restaurant, which she loves because of its freedom from the fixed routine of the seasons and of the farming day that she has known all her life: 'there was nothing time-bound… the traffic kept moving. Snow and rain were reduced to scenery… the noise was the same… I saw this as my afterlife, and for a long time it didn't occur to me that it contained a future.' But she is ultimately pulled back by the ties that binder, haunted even by the family that never existed, as she considers when thinking of her lost children 'I see one of my five children on the street, an eleven-year-old, a thirteen-year-old, a fifteen-year-old, a nineteen-year-old, a twenty-two year old' and also of her 'dead young self.'

This novel is relentlessly bleak, and not one I found easy to read or tempting to return to. Smiley's comparison to Icelandic sagas is apt, and there are certainly echoes of the modern Icelandic classic, Halldor Laxness's Independent People, which is also one of Smiley's favourite novels. A Thousand Acres demonstrates the deadweight of land ownership and of fierce family expectations as strongly as Laxness's tale of Guðbjartur Jónsson. Annie Proulx has also drawn on

Icelandic inspiration in her tales of rural Wyoming in Close Range. But

there are also reminders of Alice Munro's ability to evoke a life in the space

of a few pages. I have known about Smiley's work for a long time, but never

read anything by her before this; I'm glad to have read it, although I might

not read it again.

This book was the second I was sent for my Mr B's Reading Year. My dad is a great fan of Jane Smiley, so I was pleased to be given a reason to finally try one of her novels, and I remember him relating the story of King Lear to me after he read this novel when I was a young teenager!

This book was the second I was sent for my Mr B's Reading Year. My dad is a great fan of Jane Smiley, so I was pleased to be given a reason to finally try one of her novels, and I remember him relating the story of King Lear to me after he read this novel when I was a young teenager!

The premature death of Barry Fairbrother, a deservedly popular parish councillor for the rural town of Pagford, has a more significant impact than any of its inhabitants would have thought when Barry first collapses on his way out to dinner with his wife Mary. The occasional clunkiness of JK Rowling's style is never more apparent than when she is writing plot-important action, and this novel stutters awkwardly into life with its cliched description of Barry's last moments: 'Barry was lying motionless and unresponsive on the ground in a pool of his own vomit; Mary was crouching beneath him, the knees of her tights ripped, clutching his hand, sobbing and whispering his name.' However, it is Rowling's treatment of Barry's legacy that was one of the major factors in convincing me that this is an appealing, engrossing and meaningful work of fiction, despite its flaws. Although Barry narrates only the first two and a half pages of this long novel, his example serves as a refreshing contrast to the indifference and spite that most of the inhabitants of Pagford display at one point or another. Importantly, though, Rowling does not lazily depict Barry as an absent saint, but is careful to let us know exactly why Barry could do what he did and why it is so difficult for anyone to follow in his footsteps. I was reminded that Rowling trained as a teacher when one of Barry's colleagues makes this pitch-perfect observation: 'What was it that Barry had had? He was always so present, so natural, so entirely without self-consciousness. Teenagers, Tessa knew, were riven with the fear of ridicule. Those who were without it, and God knew there were few enough of them in the adult world, had natural authority among the young; they ought to be forced to teach.'

The reason I found this passage so resonant, I think, is that not only is it completely accurate about the qualities you need to work with young people, but because it is clear by this point in the novel that most of the harm in Pagford comes about because the characters are so afraid. Gavin, dating a kind and intelligent social worker, Kay, has encouraged her to uproot herself and her daughter from their London life then treated her with indifference since because he is too scared to tell her he does not love her. Sukhvinder, a teenage girl from the town's only Sikh family, is so terrified of letting her parents down and what to do about the cyberbulling she is suffering via Facebook that she takes to cutting herself. Samantha, owner of a failing bra shop and participant in a failing marriage, is so unable to face up to her financial difficulties and all the things she cannot say to her husband that she takes to fantasising about a teenage boy from the latest hit boy band. And most tragically of all, Krystal, a sixteen-year-old who is struggling to hold her family together as her mother battles with heroin addiction and social services threaten to take her small brother Robbie into care, is so frightened of the future that she unwittingly sets off a train of events that will make things even worse.

When I began this novel, I feared that Rowling had not played to her strengths, so determined to demonstrate that she had moved on from Harry Potter that this story would flop, but surprisingly, she leaves herself ample space to do what she is best at. Although this is not a plot-driven novel, Rowling's skill at handling multiple threads comes in increasingly handy as the narrative becomes more complex and small details from one character's story become crucial to another's. Her ability to create memorable characters that the reader cares about strongly is also evident. Although her characters are not exactly complex - even the individuals who get the most screen time, like Krystal, do not really develop - they are more than sketches. Most peculiarly, Rowling's skill at creating a world that the reader wants to continue living in, that they do not want to end, is a major factor in making this overlong novel gripping. This is peculiar because nobody wants to live in a town like Pagford - Rowling effectively skewers its narrow-mindedness and bigotry throughout - and yet this novel never becomes depressing, even throughout its melodramatic ending. In a way, putting the central plotline aside, Rowling does stick to form by rewarding the good and punishing the bad, and perhaps this is why this studiously 'realistic' novel is more satisfying than it ought to be.

This isn't a novel that does anything terribly original, but it solidly delivers on what it promises, and manages to make local politics much more interesting than earlier models of this 'slice of life' narrative - Winifred Holtby's South Riding comes to mind - have achieved. I'm now keen to read Rowling's The Cuckoo's Calling, as I think she may find an even more natural home in crime fiction; and I'd like to escape to another of her worlds.

The Goldfinch, for me, was one of those rare novels where my judgement of it utterly changed after reading the second half. Although, like any novel this length, it is an imperfect beast, and, not like all novels this length, it could do with losing a hundred pages or so from its first half, I think it was still one of the best books I've read this year. It was an inspired choice by the publishers to include a decent, if small, reproduction of the painting at the beginning of the text. As I was reading, I kept returning to Fabritius's bird and finding new meaning in it, although I have not seen the original, and by the end of the novel, I could almost see the goldfinch taking flight, catching its foot against the chain, circling back down, then beginning again. This novel does not simply become much more gripping as Theo attains adulthood and becomes mixed up in the murky world of crooked antiques dealing and art theft; it becomes much more resonant, as the many sins of Theo's adolescence continue to haunt him. As he says of the goldfinch near the end of the novel, 'what if that particular goldfinch (and it is very particular) had never been captured or born into captivity, displayed in some household where the painter Fabritius was able to see it? It can never have understood why it was forced to live in such misery…' The two tokens that remain from the moments before Theo's mother's death, the painting itself and the red-haired girl, Pippa, haunt, torture and comfort him throughout the novel, even though he might not have given either of them a second glance if not for the explosion. At the end of the novel, Theo puts forward his thesis that life is an inevitable misery from which we can nevertheless glean some joy; but I couldn't help worrying at the edges of what, for me, is a much more tragic reading, that this is true but only for some of us, and that Theo is a chained bird. Although it seems likely that his mother's death was indeed the catalyst for everything that followed, I found myself remembering as I finished this novel that he and his mother had been off to a disciplinary meeting due to Theo's hanging around with the wrong crowd before the explosion happened, and that perhaps he was doomed from the start, although not doomed to fly and fall in precisely the same way. Tartt paints on a huge canvas, and this novel will certainly be worth re-reading.

My opinion of The Luminaries, on the other hand, has remained as high as it was when I discussed the first half of the book. The thing I find particularly impressive is, ironically, how it is such a flawed mess of a text in some ways - the reader struggles to keep track of the huge cast of characters and the plot is so complex that Catton herself realises the necessity of frequent recapping. And yet, there is something magnetic about it. I've made no secret of the fact that I prefer big, ambitious, untidy novels to perfectly executed, self-contained novellas, and this is one of the reasons why. The Luminaries is a novel that you feel you can really get inside, explore, and re-read over and over again; the tightly-interwoven plot is not a turn-off, but a challenge. It takes great skill to pull such a thing off without completely alienating the reader, and although I dismissed comparisons to Wilkie Collins earlier, there is something of The Moonstone about the solution to Catton's mystery. However, Catton also has what The Moonstone - not my favourite Collins novel - lacks; a fully-rounded cast who never fall into cipher or cliche. (I still remember how annoying I found the caricature of Miss Clack and the idealised Rachel Verinder.) I particularly appreciated how, despite the range of narrators, the central cast are only ever seen through the eyes of others. Anna Wetherell is a particularly fascinating subject to watch in this way; as new revelations come to light, her character alters, until she finally does get to speak for herself late in the novel. Catton also handles a sub-current of the supernatural with immense style, leaving enough room for doubt but enough hints to send a shiver up one's spine. Superb storytelling and a worthy winner of the Booker. (And thank God it wasn't Harvest or The Testament of Mary, is what I say.)

My opinion of The Luminaries, on the other hand, has remained as high as it was when I discussed the first half of the book. The thing I find particularly impressive is, ironically, how it is such a flawed mess of a text in some ways - the reader struggles to keep track of the huge cast of characters and the plot is so complex that Catton herself realises the necessity of frequent recapping. And yet, there is something magnetic about it. I've made no secret of the fact that I prefer big, ambitious, untidy novels to perfectly executed, self-contained novellas, and this is one of the reasons why. The Luminaries is a novel that you feel you can really get inside, explore, and re-read over and over again; the tightly-interwoven plot is not a turn-off, but a challenge. It takes great skill to pull such a thing off without completely alienating the reader, and although I dismissed comparisons to Wilkie Collins earlier, there is something of The Moonstone about the solution to Catton's mystery. However, Catton also has what The Moonstone - not my favourite Collins novel - lacks; a fully-rounded cast who never fall into cipher or cliche. (I still remember how annoying I found the caricature of Miss Clack and the idealised Rachel Verinder.) I particularly appreciated how, despite the range of narrators, the central cast are only ever seen through the eyes of others. Anna Wetherell is a particularly fascinating subject to watch in this way; as new revelations come to light, her character alters, until she finally does get to speak for herself late in the novel. Catton also handles a sub-current of the supernatural with immense style, leaving enough room for doubt but enough hints to send a shiver up one's spine. Superb storytelling and a worthy winner of the Booker. (And thank God it wasn't Harvest or The Testament of Mary, is what I say.)

See this post for the first half of my review of The Goldfinch and this post for the first half of my review of The Luminaries.

Having successfully completed last year's New Year's Resolution to post every Friday on this blog, I thought I'd mix things up again for 2014. I'll be keeping my regular Friday posts, but adding a Monday Musings slot where I briefly discuss topical book and writing-related questions (e.g. is 'writing what you know' necessarily a good thing? What do we mean by 'showing not telling'?) Wednesday will become a 'wild card' day where I may post or not, depending on how much I've been reading recently - I hope to occasionally do reading round-ups, for example.

Having successfully completed last year's New Year's Resolution to post every Friday on this blog, I thought I'd mix things up again for 2014. I'll be keeping my regular Friday posts, but adding a Monday Musings slot where I briefly discuss topical book and writing-related questions (e.g. is 'writing what you know' necessarily a good thing? What do we mean by 'showing not telling'?) Wednesday will become a 'wild card' day where I may post or not, depending on how much I've been reading recently - I hope to occasionally do reading round-ups, for example.