Suzanne Moore's recent Guardian article, 'Why I hate Bridget Jones', pretends to be an attack on the 'anti-feminist' character of Bridget Jones, but it's really an attack on her fans; the 'vapid' women who read chick lit and identify with Bridget, who feel they need a 'man to define them' and like shopping for new shoes. Of course Bridget is anti-feminist, she argues, because she's not an independent woman, she's selfish and self-obsessed, and her worries are trivial (although I'm not sure why Moore believes that the solution to women's worries about when it is best to have a baby is 'just get on with it'). The problem with this is that Moore is implicitly saying that all the women who do enjoy Bridget Jones, romcoms and shopping are just not good enough to be feminists; they must be shallow and stupid, unable to appreciate the collective power of feminist organisation, and - Well, I'm not sure what she wants to do with these awful women, really. Should we just ignore them and hope they are never ever represented ever?

Suzanne Moore's recent Guardian article, 'Why I hate Bridget Jones', pretends to be an attack on the 'anti-feminist' character of Bridget Jones, but it's really an attack on her fans; the 'vapid' women who read chick lit and identify with Bridget, who feel they need a 'man to define them' and like shopping for new shoes. Of course Bridget is anti-feminist, she argues, because she's not an independent woman, she's selfish and self-obsessed, and her worries are trivial (although I'm not sure why Moore believes that the solution to women's worries about when it is best to have a baby is 'just get on with it'). The problem with this is that Moore is implicitly saying that all the women who do enjoy Bridget Jones, romcoms and shopping are just not good enough to be feminists; they must be shallow and stupid, unable to appreciate the collective power of feminist organisation, and - Well, I'm not sure what she wants to do with these awful women, really. Should we just ignore them and hope they are never ever represented ever?

Bridget Jones (and here I speak of the first two novels and the first film, not the appalling second film and the third novel, which I haven't read) is not chick lit. It's social satire. I don't say this because I think there is anything shameful about reading and enjoying so-called chick lit - I certainly do - but because this pigeonholing of the novels as chick lit is part of the problem. As even Moore admits, the novels are genuinely funny, and Helen Fielding uses Bridget's unreliable narration to make them so. Bridget is intentionally presented as confused, often selfish, and a little intellectually challenged, because that's how the character was designed to be; it's not as if she was trying to fit the 'strong independent woman' mould and fell out the other side. Bridget is not a feminist, because it was never the author's intention to depict her as a feminist icon; but (and Moore seems to miss this crucial distinction) one can depict anti-feminist characters in a novel that is feminist, or at least not hostile to feminism. Indeed, if anything, Fielding reminds us why we need feminism, because minus feminism and plus the empty rhetoric of empowerment, you get Bridget Jones.

To this extent, Moore and I are in agreement. But the answer to this isn't to trash Bridget, and the thousands of women like me who love the novels and the first film. Instead, we should question why Bridget Jones has been presented as 'everywoman' when she clearly is not. And we should recognise why her story is so enjoyable, and so comforting. Bridget doesn't give her readers any answers, but she's in the habit of asking the right questions - from why the choice for women seems to be between her miserable single life and her friend Magda's miserable full-time-motherhood, to protesting that it seems to be OK for everyone to ask her 'how's your love life?' when no-one ever inquires into the state of other people's marriages. I'd go as far as to say, in fact, that Moore's article is far more anti-feminist than Bridget has ever been, because she goes out of her way to criticise other women who may have enjoyed the books or the film, without ever considering what they might have got out of it, and assuming that Bridget's 'fans' are just like her. As far as I can see, feminism isn't about criticising other women for bowing to social pressures; it's about asking why women feel that they need a man to complete them. If Moore is concerned that Bridget has been presented as some sort of role model, then she should attack the media - not the character, her readers, or her viewers.

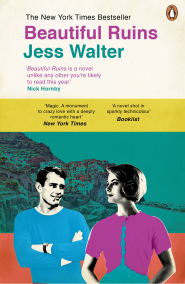

I've used the original book cover for this blog post, rather than the raft of images of Renee Zellweger, because I think it's a good reminder that Bridget didn't start out as a chick-lit heroine. Rather, she was 'a creation of comic genius', according to Nick Hornby. (As I've said before, one wonders what might have been the fate of his novels were he Nicola Hornby). It's a shame that now it's so hard to come to the novel afresh and read it as a comedy - not a romcom or a love story - because that's what it is. And Bridget herself is a key target for her author's social critique.

[In the interests of full disclosure, I have to admit that I was so inspired by Helen Fielding's novels that I once wrote a Harry Potter fanfic in the style of Bridget Jones. This masterpiece can be read here. Regardless of literary quality, it was enormous fun!]